Economic and market overview

Global

Well into the second year of the global Covid-19 pandemic, the ferocity and persistence of the virus has surprised most people – experts and the public alike.

Asia, a region that seemed to get through the early stages of the pandemic relatively unscathed, has suffered under the spread of a new wave of infections of the Delta variant of the coronavirus. This may cut short the global economic recovery that we’ve seen take place since the last quarter of 2020. The key to getting through this hurdle to economic growth is the success of vaccination programs around the world. If the efforts to inoculate significant portions of the global adult population are not derailed, the most recent hiccup in economic activity will be short-lived. This is illustrated by data from the United Kingdom where more than 95% of the adult population now have anti-bodies – be it from the vaccine or having contracted Covid-19. Evidence is unambiguous – the vaccine provides good immunity and significantly reduces the link between infection and hospitalisation.

According to Glyn Owen, Investment Director at Momentum Global Investment Management in London, a Covid-19 setback to the global economic recovery is temporary in nature. At their recent Think Tank, he said that it may delay the recovery, but is unlikely to derail it in totality. In the last month alone, over 1 billion doses of the vaccine have been administered, and at this rate immunity (even if not complete) is not too far off in developed markets. Progression of vaccination programs in emerging markets has been much slower, but its progression nonetheless.

setback to the global economic recovery is temporary in nature. At their recent Think Tank, he said that it may delay the recovery, but is unlikely to derail it in totality. In the last month alone, over 1 billion doses of the vaccine have been administered, and at this rate immunity (even if not complete) is not too far off in developed markets. Progression of vaccination programs in emerging markets has been much slower, but its progression nonetheless.

Owen further noted that this economic crisis had an impact on both the supply and demand sides of the global economy, so shortages of some goods and rising costs may provide a headwind into 2022. Core inflation measures have risen to 30-year highs in the United States this year. The big question is whether this will be temporary in nature (as the US Federal Reserve believes it will be) or if it will be persistent with negative consequences for bond and equity markets. For now, markets lean towards the transitory camp rather than expecting structurally higher inflation. In fact, in Europe and Japan fears about deflation outweigh the risk that the current loose monetary and fiscal policy will lead to hyper-inflation.

China also featured in the news this month but not always for the right reasons. In a recent webinar Kevin Lings, Chief Economist of STANLIB cited a few recent developments which may impact the Chinese economy. Although small in number of people infected, they have had a few new domestic Covid-19 outbreaks followed by harsh lockdown measures, which has had a significant impact on economic activity in those regions. Coupled with the impact that prolonged semiconductor shortages have on manufacturing in China, their campaign to reduce carbon emissions (especially in steel, cement, and aluminum production) and Premier Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” agenda which attempts to narrow the gap between rich and poor, the Chinese economy may not be as successful as before in being the driving force behind global economic growth.

Much of the risks to the global economic recovery that are mentioned above are reflected in equity market valuations. Emerging economies may yet recover faster than currently anticipated which may see a flow of capital from expensively valued developed markets (especially in the United States) to much more attractively priced developing markets. Investors will, however, do well to remain well diversified in their approach to portfolio construction as no particular outcome is certain. Once again patient investors are likely to be rewarded by sticking to tested investment strategies rather than trying to successfully time their exposure to riskier assets (such as equities and property).

South Africa

The South African Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to leave the repurchase rate unchanged, keeping it at 3.5%.

This is the seventh consecutive meeting where interest rates were kept in check with all the members of the committee voting for no change. The SARB’s quarterly projection model (which is used as a guideline to set monetary policy) still indicates an increase of 25 basis points in the fourth quarter of 2021 and further increases in each quarter of 2022 and 2023. That amounts to total rate increases of 2.25% over the next 27 months. It’s important to note that the QPM is not blindly followed, but it certainly provides an indication of the trend of interest rates in the future. The market is not expecting rate increases to the quantum predicted by the QPM but it’s fair to say that, with the information at hand, the next move will be up.

The rate of Covid-19 vaccinations in South Africa has remained quite stable with between 2% and 3% of the adult population receiving a dose every week. At this rate, about 60% of the adult population would be vaccinated by middle December, which will leave us short of the 70% target set by the Department of Health. However, this does not consider the portion of the population that has anti-bodies after having contracted the disease, so there may just be enough of a herd immunity to not lead to further lockdowns during South Africa’s summer holidays.

middle December, which will leave us short of the 70% target set by the Department of Health. However, this does not consider the portion of the population that has anti-bodies after having contracted the disease, so there may just be enough of a herd immunity to not lead to further lockdowns during South Africa’s summer holidays.

The Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) has set the date for municipal elections as 1 November 2021. The results of these elections will give an indication of the extent voters will allow the governing parties in different municipalities another chance to deliver services. National Treasury provides enough funds to local governments to operate and it’s now up to the public to put capable politicians in place to guide these funds away from corrupt pockets into proper infrastructure spend and the delivery of basic services to residents.

Back to the economic front: Visio Capital reports that headline inflation for August accelerated to 4.9% from 4.6% in July with transport prices making up the bulk of the increase in inflation having risen for the first time in four months. Food inflation also ticked up and is now at its highest rate in over four years. Both food and transport inflation are likely to remain elevated for the next few months resulting in headline inflation hovering around current levels before moving back to the middle of the inflation target range of 4.5%. In a speech he delivered at Stellenbosch University the governor of the Reserve Bank, Lesetja Kgnayago made a case for targeting 3% as the long-term level of inflation of South Africa. Given their success in keeping inflation within its set limits since inflation targeting was introduced in South Africa over 21 years ago, the governor’s comments should not go unnoticed. South Africans may be in for a prolonged period of low inflation which will lead to structurally lower costs of debt servicing. This could be very beneficial to the economic growth so dearly needed to address South Africa’s unemployment rate and the government’s ability to reduce its debt to GDP ratio.

Looking forward, leading economic indicators, on aggregate, are looking better suggesting that the local recovery still has momentum. The South African economy is likely to return to pre-pandemic levels sooner than previously expected. However, signs of the global economic growth slowdown (mentioned on the previous page) pose a risk to the local economy which is heavily dependent on commodity prices. Faster economic reforms and encouraging investment spend (especially from foreigners) will be required to keep the growth momentum.

Market Performance

September was a challenging month in global markets, as both developed and emerging market equity indices finished the month lower. Laurium Capital reports that data out of China continued to be weak as Covid lockdowns, pollution control measures, and power shortages slowed economic activity. There was also an elevated risk of insolvency at Evergrande, a highly indebted Chinese property developer. These concerns coincided with the ongoing semiconductor chip supply shortage (emanating mainly from Malaysian lockdown restrictions) and constrained logistics capacity in nearly every supply node. As a result, global production output slowed down somewhat from the fast pace of growth we have seen since the Covid activity trough in early 2020.

South African equity indices ended the month lower. The All Share Index returned -3.1% for the month, with most of the pain coming in Resources, which lost nearly 10% in September. Heavyweights Naspers and Prosus again lost ground as Tencent and other related Chinese technology stocks remained under selling pressure. SA banks were positive performers, driven higher by solid results and improved credit losses. Small-cap stocks bucked the trend and gained nearly 6% during the month. Year to date this sector has delivered 46.3% to investors who held on to their positions at the bottom of the market capitalisation spectrum.

the pain coming in Resources, which lost nearly 10% in September. Heavyweights Naspers and Prosus again lost ground as Tencent and other related Chinese technology stocks remained under selling pressure. SA banks were positive performers, driven higher by solid results and improved credit losses. Small-cap stocks bucked the trend and gained nearly 6% during the month. Year to date this sector has delivered 46.3% to investors who held on to their positions at the bottom of the market capitalisation spectrum.

Within commodity markets, the picture was also mixed. The reduction in Chinese steel production caused iron ore prices to fall further, while palladium and rhodium prices continued to suffer the short-term impact of closed auto factories. Conversely, the aluminum price surged following a coup in Guinea, a large bauxite producer. Brent crude oil marched higher, breaching $80/barrel for the first time since 2018 as supplies of crude remained tight. This lead to the Sasol share price gaining more than 27% during the month – it has now more than doubled since the start of the year.

A strong US dollar, falling metal prices, and higher energy prices put pressure on the rand which lost 4% during the month. This, as well as higher US Treasury yields, reduced foreign investor appetite for South African bonds resulting in large selling (R35.2bn) pushing yields higher and prices lower (-2.1%).

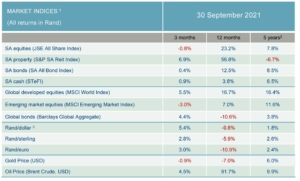

- Source: Factset

- All performance numbers in excess of 12 months are annualised

- A negative number means fewer rands are being paid per US dollar, so it implies a strengthening of the rand.

Commentary – The World is not Enough

With the recent release of “No time to die”, the 25th movie in the popular James Bond franchise, it was very tempting to write about the effects that improving mortality rates have on global demographics. We however opted to go back in time to “The world is not enough”, the 19th movie in the 007 series. This month we’re having a look at the quantum of global wealth and who owns it.

Credit Suisse recently published their annual global wealth1 report. They state that wealth creation in 2020 was largely immune to the challenges facing the world due to the actions taken by governments and central banks to mitigate the economic impact of COVID-19. Total global wealth grew by 7.4% (to USD 418 trillion) and wealth per adult rose by 6% to reach another record high of nearly USD 80 000. Overall, the countries most affected by the pandemic have not fared worse in terms of wealth creation.

USD 418 trillion. That’s a lot of wealth. It consists mainly of property (the property market in China is believed to be over USD 50 trillion and over USD 36 trillion in the United States) and financial assets such as shares, cash (in the form of bank accounts). All the gold ever mined amounts to an eighteen-meter cube (just short of 200 000 tonnes) and is worth around USD 11 trillion at the prevailing gold price. The total cryptocurrency market reached a capitalisation of nearly USD 2.4 trillion in May this year but has since fallen back to below USD 2 trillion. Global equity markets account for about USD120 trillion of global wealth.

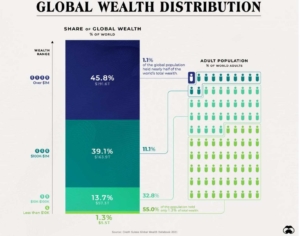

Statistics can hide a lot of detail. An average level of net wealth of around USD 80 000 per adult does not sound too shabby – that’s R1.2 million for every person over the age of 18. Given that the wealthiest people on earth (either Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos, depending on what happens to Tesla’s and Amazon’s share prices) are worth nearly USD 200 billion each, it stands to reason that there is a very unequal distribution of wealth among the citizens of the world as the graphic below shows:

1 – Net worth, or “wealth,” is defined as the value of financial assets plus real assets (principally housing) owned by households, minus their debts. This corresponds to the balance sheet that a household might draw up, listing the items which are owned, and their net value if sold. Private pension fund assets are included, but not entitlements to state pensions. Human capital is excluded altogether, along with assets and debts owned by the state (which cannot easily be assigned to individuals).

Commentary – The World is not Enough (continued)

Looking ahead, Credit Suisse states that global wealth is projected to rise by 39% over the next five years, reaching USD 583 trillion by 2025. Low- and middle-income countries are responsible for 42% of the growth, although they account for just 33% of current wealth. Wealth per adult is projected to increase by 31%, passing the watershed mark of USD 100,000. The number of millionaires will also grow markedly over the next five years, reaching 84 million, while the number of Ultra High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs, USD 50 million upward) should reach 344,000.

The report also highlights the wealth of the largest economies on each continent. For Africa, the focus is on Nigeria and South Africa. Wealth per adult amounted to a little over USD 20 300 in South Africa at the end of 2020, which was much higher than the Nigerian figure of about USD 6 450. South Africa is the outlier here: the average for Africa as a whole is USD 7 371. But there has been some convergence over the last two decades. In 2007, for example, the corresponding levels were USD 1 950 in Nigeria and USD 25 200 in South Africa, i.e. wealth per adult in South Africa was 13 times that in Nigeria in 2007, compared to a multiple of about three times in 2020.

Total South African net wealth stood at USD 800 billion at the end of 2020 (with financial assets making up about two-thirds of this). Total wealth at the southern tip of Africa is roughly equal to the net wealth of the 5 richest people on earth (and no, Mr. Musk is not classified as South African as many of us may claim):

So will the world ever be enough? We’ll phone Elon and let you know what he says…

Source: Credit Suisse Research Institute Global Wealth Report 2021