Economic and Market Overview

June 2022

Global

Economic growth around the globe is likely to be lower than was anticipated at the start of the year. Combined with the war in Ukraine, strict COVID-19 lockdowns in China, higher inflation for longer, and steeper than expected interest rate increases, it has had a significant negative impact on the expected earnings for companies which has been reflected in recent share price movements.

In a recent report, RMB Global Markets adds that the global growth outlook is vulnerable to both the impact of elevated commodity prices and increasingly restrictive monetary policies. Their base case is that output in advanced economies will slow, most notably in Europe, which is directly impacted by the war. Some resource-rich developing economies will continue to benefit from the higher commodity prices, but the net export position will be the differentiator.

In their May 2022 Global Outlook, the Blackrock Investment Institute identifies three investment themes. In the first theme, “Living with inflation”, they note that central banks are facing a growth-inflation trade-off. Hiking interest rates too aggressively risks triggering a recession, while not tightening enough may cause runaway inflation. The US Federal Reserve has made it clear it is ready to dampen growth, which is partly why investment markets have retreated significantly in recent months. Their second theme pivots around cutting through all the confusion. The Russia-Ukraine conflict has aggravated inflation pressures. Trying to contain inflation will be costly to growth and jobs. They see a worsening macro outlook due to the Federal Reserve’s hawkish stance, the commodities price shock, and China’s growth slowdown. In the third instance, they highlight the navigation towards net-zero, where carbon emissions equal carbon recycling. Climate risk is investment risk, and the narrowing window for governments to reach net-zero goals means that investors need to start adapting their portfolios. The net-zero journey is not just a 2050 story; it’s a now story. Investors should, however, be mindful of how green investments truly are – many product providers have green-washed their assets so that they could get on the bandwagon of this theme rather than providing a truly sustainable investment proposition.

banks are facing a growth-inflation trade-off. Hiking interest rates too aggressively risks triggering a recession, while not tightening enough may cause runaway inflation. The US Federal Reserve has made it clear it is ready to dampen growth, which is partly why investment markets have retreated significantly in recent months. Their second theme pivots around cutting through all the confusion. The Russia-Ukraine conflict has aggravated inflation pressures. Trying to contain inflation will be costly to growth and jobs. They see a worsening macro outlook due to the Federal Reserve’s hawkish stance, the commodities price shock, and China’s growth slowdown. In the third instance, they highlight the navigation towards net-zero, where carbon emissions equal carbon recycling. Climate risk is investment risk, and the narrowing window for governments to reach net-zero goals means that investors need to start adapting their portfolios. The net-zero journey is not just a 2050 story; it’s a now story. Investors should, however, be mindful of how green investments truly are – many product providers have green-washed their assets so that they could get on the bandwagon of this theme rather than providing a truly sustainable investment proposition.

In summary: geopolitical, monetary, and renewed supply chain shocks have led to both global bonds and equities selling off this year. According to Blackrock, there will have to be significant positive surprises to the economic outlook for equities to have a proper rebound:

South Africa

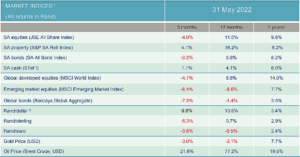

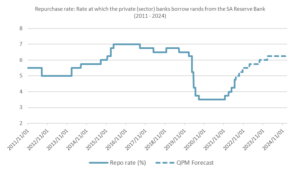

The South African Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to increase the repurchase rate by 0.5%, taking it to 4.75%.

Four members of the Monetary Policy Committee voted for this increase, with one opting for a more modest 25 basis point hike. In his statement following the meeting, the governor said that the implied policy rate path of their Quarterly Projection Model indicates gradual normalisation through to 2024. The market’s consensus view is that all else being equal, the repo rate will normalise at 6.25% in two years’ time. This is still below the policy rate of 6.5% (in 2019) before the Covid-19 pandemic significantly influenced monetary policy.

Source: South African Reserve Bank, Bloomberg

The increased cost of servicing debt that is associated with interest increases, coupled with the ever-rising cost of energy and less than reliable electricity supply will continue to weigh on the growth prospects of the South African economy. Much of this is already reflected in share price movements – if it’s in the press it’s in the price.

Despite the significant increase in fuel prices, South Africa’s inflation seems to be far more under control than in the rest of the world. The Reserve Bank expects inflation to average 5.9% in 2022, falling to 5.0% in 2023 and 4.7% in 2024.

Their growth outlook remains anything but rosy though. The economy is forecast to expand by 1.9% in both 2023 and 2024. At these rates, growth remains well below potential, impacted by loadshedding, infrastructure, and policy constraints. Investment by the government sector has weakened significantly in recent years and that of public corporations is forecast to be very modest. Household spending remains supportive, as a result of good growth in disposable income, rising asset prices, and low-interest rates. Private investment has also proven to be more resilient than previously expected. Tourism, hospitality, and construction should see stronger recoveries as the year progresses. Current assumptions are quite gloomy, which implies that modest upside surprises could spark short-term rallies. The recent arrest of two Gupta brothers in the UAE may be a small victory, but it will help in the war against corruption.

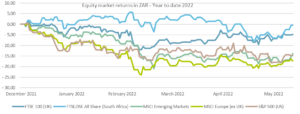

Market Performance

Markets around the world remained volatile as investors tried to navigate inflation, interest rates, supply shocks, and geopolitical turmoil in Europe. The MSCI World index, a bellwether for global developed market equities, was well down mid-month but ended May up a meager 0.2% (in US Dollars). Emerging markets fared slightly better adding 0.5% for the month, while the South African All Share Index lost 0.4% in local currency terms. These movements may seem slight, but they hide the significant mid-month market movements that we saw around the globe.

The South African equity market was supported by strong performances of some of the large-cap stocks including Anglos, Naspers, Sasol, and Glencore, as well as the banking sector which remains the best performing JSE sector in 2022. Visio Capital further reports that local bonds continued to do better than their global counterparts despite continuous foreign selling. Year-to-date local equities have far outperformed their global counterparts:

- Source: Factset

- All performance numbers in excess of 12 months are annualised

- A negative number means fewer rands are being paid per US dollar, so it implies a strengthening of the rand.

depend on the tax treatment of dividends received versus capital gains (the latter is typically a direct result of share buybacks).

depend on the tax treatment of dividends received versus capital gains (the latter is typically a direct result of share buybacks).