June 2023 In Review

-

In an interview with Business Day, Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago has suggested the central bank’s almost two-year-long fight against inflation is paying off, saying recent data showed clear signs of the reversal of the inflationary trend. SA’s annual inflation rate fell for the second month in May to 6.3%, the lowest level since April 2022, thanks to slower food and transport prices. It had hit a 13-year high of 7.8% in July 2022, driven by a combination of factors such as high fuel prices, supply chain disruptions, a weak exchange rate, power outages, an accommodative macroeconomic policy and global inflation pressures. STANLIB reports that the inflation rate is expected to drop back into the target range (3% to 6%) in the second half of the year, despite the pending large increase in the electricity price and rand weakness in May 2023.

-

A quartet of African leaders, led by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, visited Russia’s Vladimir Putin in Moscow as part of efforts to resolve the war between the two nations. According to Al Jazeera this so-called “peace mission” puzzled many observers. Aside from numerous unexpected scenarios, the leaders and some of their aides eventually made it to the Kremlin. They put forward a 10-point plan that included sending prisoners of war and children back to their countries of origin and unimpeded grain exports through the Black Sea. As it stands the effort is yet to yield any results.

-

Ahead of their meeting with the Russian president, the contingent met Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Kyiv. During a joint press conference with the African delegation, Zelenskyy reiterated that there would be no peace agreement while Russia continues to occupy parts of Ukraine, telling reporters that to allow any such dialogue is “to freeze the war, to freeze everything: pain and suffering”. While the African delegation was in Kyiv, Russian missiles shelled Ukraine, forcing the visiting group to seek cover in a bomb shelter.

-

The astonishing rebellion which Yevgeny Prigozhin, head of the Wagner mercenary group, launched against the Russian government and then suddenly aborted one day later, has raised many questions about Russian President Vladimir Putin’s grip on power. It may well have weakened the influence Prigozhin has over the Russian armed forces as well.

-

The Economist reports that investors are hoping central banks in developed markets can return inflation to their 2% targets without inducing a recession. However, history suggests that bringing inflation down will be painful. In Britain, mortgage rates are surging, causing pain to aspiring and existing homeowners alike. Rarely has America’s economy escaped unscathed as the Federal Reserve has raised rates. Moreover, the secular forces pushing up inflation are likely to gather strength. Sabre-rattling between America and China is leading companies to replace efficient multinational supply chains with costlier local ones. The demands on the public purse to spend on everything from decarbonisation to defense will only intensify, most likely leading to a structural increase in long-run inflation from the low levels seen up to 2020.

-

Reuters reported that Monday 3 July 2023 was the hottest day ever recorded globally, according to data from the U.S. National Centers for Environmental Prediction. The average global temperature reached 17.01 degrees Celsius, surpassing the August 2016 record of 16.92 ˚C as heatwaves sizzled around the world. Even Antarctica, currently in its winter, registered anomalously high temperatures. Ukraine’s Vernadsky Research Base in the white continent’s Argentine Islands recently broke its July temperature record at 8.7 ˚C.

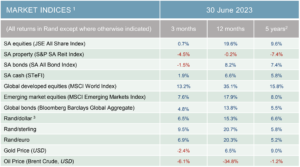

Market Performance

Global equity markets enjoyed a strong month in June, with the MSCI World Index increasing 6.1% (in US dollar terms) taking its gain for the quarter to 6.8% and to over 15% for the year. Laurium Capital reports that stronger-than-expected corporate earnings and optimism about the prospects for productivity gains associated with generative artificial intelligence (AI) boosted technology shares. It also helped to offset lingering concerns surrounding geopolitical tensions in Europe as well as between the United States and China. This AI-fueled rally has pushed the technology-heavy Nasdaq 100 Index to a 38.8% rally in USD (over 50% in rands) terms and has also lifted the S&P 500 to a 15.9% (27.9% in rands) rally in the first half of 2023. This surge has been very concentrated as it was driven by eight large technology stocks whose share prices have benefitted from their perceived future gains due to the development and or use of AI.

In the local market, equities (as measured by the JSE All Share Index) returned 1.4%, supported by a recovery in South African-focused companies as loadshedding concerns tempered over the course of the month. The waning negative sentiment towards South Africa saw the rand strengthen 4.5% to R18.73/$.

South African bonds rebounded strongly in June (up 4.6%), recovering most of the losses from May as some calm returned after sentiment around the electricity sector improved, and the immediate threat of economic sanctions against South Africa subsided.

- Source: Factset

- All performance numbers in excess of 12 months are annualised

- A negative number means fewer rands are being paid per US dollar, so it implies a strengthening of the rand.

Did you know?

Have you ever thought where the custom of paying interest on a loan comes from? The exact rise of interest as a concept is unknown, though its use in Sumeria argues that it was well established as a concept by 3000 BC, if not earlier. Historians believe that the concept in its modern sense may have arisen from the lease of animals or seeds for productive purposes. The argument that acquired seeds and animals could reproduce themselves was used to justify interest, but various ancient religious prohibitions against usury represented a “different view”. In fact, religious views controlled the level and way interest rates were charged for many centuries.

The first written evidence of compound interest dates roughly 2400 BC. The annual interest rate was around 20%. While the traditional Middle Eastern views on interest were the result of the urbanized, economically developed character of the societies that produced them, the new Jewish prohibition on interest showed a pastoral, tribal influence. In the early 2nd millennium BC, given silver used in exchange for livestock or grain could not multiply of its own, the Laws of Eshnunna instituted a legal interest rate, specifically on deposits of dowry. Early Muslims called this riba, translated today as the charging of interest.

The First Council of Nicaea, in 325, forbade clergy from engaging in usury which was defined as lending on interest above 1 percent per month. Ninth-century ecumenical councils applied this regulation to lay people. Catholic Church opposition to interest hardened in the era of scholastics, when even defending it was considered a heresy. St. Thomas Aquinas, the leading theologian of the Catholic Church, argued that the charging of interest is wrong because it amounts to “double charging”, charging for both the thing and the use of the thing.

In the medieval economy, loans were entirely a consequence of necessity (bad harvests, fire in a workplace) and, under those conditions, it was considered morally reproachable to charge interest. It was also considered morally dubious, since no goods were produced through the lending of money, and thus it should not be compensated, unlike other activities with direct physical output such as blacksmithing or farming. For the same reason, interest has often been looked down upon in Islamic civilization, with almost all scholars agreeing that the Qur’an explicitly forbids charging interest.

In the Renaissance era, greater mobility of people facilitated an increase in commerce and the appearance of appropriate conditions for entrepreneurs to start new, lucrative businesses. Given that borrowed money was no longer strictly for consumption but for production as well, interest was no longer viewed in the same manner.

The first attempt to control interest rates through manipulation of the money supply was made by the Banque de France in 1847. To this day, most central banks around the world use interest rates to attempt to, among others, influence inflation and economic growth. It may not be influenced by religious (or even moral views) anymore, but central bank policy can often be as contentious as differences in beliefs.

The modern view of interest is that the rate of interest is the price of credit, and it plays the role of the cost of capital. In a free market economy, interest rates are subject to the law of supply and demand of the money supply, with central banks influencing money supply through their official interest rate and other monetary policies.

Source: BBC, Wikipedia