Skip to content

Economic and Market Overview – August 2022

Economic and Market Overview

August 2022

Global

From inflation to recession. This was a dominant theme in macro-economic analysis in July.

Inflation in most developed markets has likely peaked and attention has now shifted to the likelihood of recessions occurring in the major economies around the world. Global economic growth in a post Covid-19 world has already been reined in with interest rate increases by almost every central bank. As debt servicing costs (for the public and private sector alike) are soaring, so economic activity seems to slow down.

In a recent update to their Global Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that a tentative recovery in 2021 has been followed by increasingly gloomy developments in 2022 as risks began to materialize. Global output contracted in the second quarter of this year, owing to downturns in China and Russia, while consumer spending in the United States undershot expectations. Several shocks have hit a world economy already weakened by the pandemic: higher-than-expected inflation worldwide – especially in the United States and major European economies – triggering tighter financial conditions; a worse-than-anticipated slowdown in China, reflecting COVID- 19 outbreaks and lockdowns; and further negative spillovers from the war in Ukraine.

The baseline forecast is for Global growth to slow from 6.1 percent last year to 3.2 percent in 2022. Lower growth earlier this year, reduced household purchasing power, and tighter monetary policy drove a downward revision of 1.4 percentage points in the United States. In China, further lockdowns and the deepening real estate crisis have led growth to be revised down by 1.1 percentage points, with major global spillovers. And in Europe, significant downgrades reflect spillovers from the war in Ukraine and tighter monetary policy. Global inflation has been revised upwards due to food and energy prices as well as lingering supply-demand imbalances and is anticipated to reach 6.6 percent in advanced economies and 9.5 percent in emerging markets and developing economies this year. In 2023, disinflationary monetary policy is expected to bite, with global output growing by just 2.9 percent.

tighter monetary policy drove a downward revision of 1.4 percentage points in the United States. In China, further lockdowns and the deepening real estate crisis have led growth to be revised down by 1.1 percentage points, with major global spillovers. And in Europe, significant downgrades reflect spillovers from the war in Ukraine and tighter monetary policy. Global inflation has been revised upwards due to food and energy prices as well as lingering supply-demand imbalances and is anticipated to reach 6.6 percent in advanced economies and 9.5 percent in emerging markets and developing economies this year. In 2023, disinflationary monetary policy is expected to bite, with global output growing by just 2.9 percent.

The risks to the outlook are overwhelmingly tilted to the downside. The war in Ukraine could lead to a sudden stop of European gas imports from Russia; inflation could be harder to bring down than anticipated either if labor markets are tighter than expected or inflation expectations unanchor; tighter global financial conditions could induce debt distress in emerging markets and developing economies; renewed COVID-19 outbreaks and lockdowns, as well as a further escalation of the property sector crisis, might further suppress Chinese growth; and geopolitical fragmentation could impede global trade and cooperation. This is not a rosy outlook by any stretch of the imagination.

With increasing prices continuing to squeeze living standards worldwide, taming inflation should be the first priority for policymakers. Tighter monetary policy will inevitably have real economic costs, but delaying will only exacerbate them. Targeted fiscal support can help cushion the impact on the most vulnerable, but with government budgets stretched by the pandemic and the need for a disinflationary overall macroeconomic policy stance, such policies will need to be offset by increased taxes or lower government spending. Tighter monetary conditions will also affect financial stability, requiring judicious use of macroprudential tools and making reforms to debt resolution frameworks all the more necessary. Policies to address specific impacts on energy and food prices should focus on those most affected without distorting prices. And as the pandemic continues, vaccination rates must rise to guard against future variants. Finally, mitigating climate change continues to require urgent multilateral action to limit emissions and raise investments to hasten the green transition. The risk for policy mistakes remain high, but this is not a new risk. As always – if it’s in the press, it’s in the price. Against such a gloomy backdrop there will be great investment opportunities for active investors.

South Africa

The South African Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to increase the repurchase rate by 0.75%, taking it to 5.5%.

Three members of the Committee preferred the announced increase. One member preferred a 100 basis points increase and the remaining member preferred a 50 basis point increase. This is still below the policy rate of 6.5% in 2019 before Covid-19.

In his statement governor Lesetja Kganyago noted that the South African economy expanded by 4.9% last year. This year the economy is expected to grow by 2.0%, revised up from 1.7%. This bucks the global trend, albeit if off a low base. Growth in output in the first quarter of this year surprised to the upside at 1.9%, stronger than the 0.9% expected at the time of the May meeting of the MPC. Despite this outcome, flooding in Kwa-Zulu Natal and more extensive load-shedding are expected to result in a contraction of 1.1% in the second quarter.

The South African economy is forecast to expand by 1.3% in 2023 and by 1.5% in 2024. This is below the SARB’s previous projection (in May 2022) of 1.9% for both years. Despite these downward revisions, economic growth remains above a low rate of potential. Private investment has strengthened on the back of the recovery, but public sector investment remains weak. Household spending remains supportive of growth but is likely to soften next year due to higher inflation, lower asset prices, and rising interest rates. Tourism, hospitality, and construction should see stronger recoveries as the year progresses.

Despite these downward revisions, economic growth remains above a low rate of potential. Private investment has strengthened on the back of the recovery, but public sector investment remains weak. Household spending remains supportive of growth but is likely to soften next year due to higher inflation, lower asset prices, and rising interest rates. Tourism, hospitality, and construction should see stronger recoveries as the year progresses.

As a result of higher global food prices, local food price inflation has also been revised upwards and is now expected to be 7.4% in 2022, and 6.2% in 2023. The food price inflation forecast for 2024 is unchanged at 4.2%. This may not seem as high as anecdotal evidence may suggest and is a small glimmer of hope as the figure is much lower than in many developed markets.

The Reserve Bank’s forecast of headline inflation for this year is revised higher to 6.5% (from 5.9% at their meeting in May). Higher food, fuel, and core inflation are expected to keep headline inflation elevated at 5.7% in 2023. Headline inflation of 4.7% is expected in 2024, getting very close to the Bank’s long-term inflation target of 4.5%. Having said that, the risks to the inflation outlook are assessed to the upside. Global producer price and food price inflation continued to surprise higher in recent months and may do so again. Russia’s war in Ukraine is likely to persist for the rest of this year and may have significant further effects on global prices. Oil prices increased strongly from the start of the war and may rise further as stresses in energy markets intensify. Electricity and other administered prices continue to present short- and medium-term risks. Given below-inflation assumptions for public sector wage growth and higher petrol and food price inflation, considerable risk still attaches to the now elevated nominal wage forecast.

It’s clear that the Reserve Bank is adamant to contain inflation with their latest interest rate increase. Guiding inflation back towards the mid-point of the target band can reduce the economic costs of high inflation and enable lower interest rates in the future. Achieving a prudent public debt level, increasing the supply of energy, moderating administered price inflation, and keeping wage growth in line with productivity gains would enhance the effectiveness of monetary policy and its transmission to the broader economy.

Reliable electricity supply without exorbitant price increases will play a major role in supporting economic growth and bringing inflation in line again. In this month’s commentary, we take a deeper dive into the efforts to bring the national electricity supplier out of its various challenges.

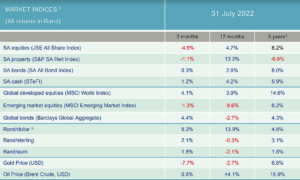

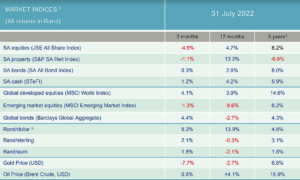

Developed Market equities and bonds rebounded strongly in July as the focus moved from rising inflation to slower economic growth. The prospect of the US Federal Reserve not raising its policy rate as much as previously thought has also added to optimism.

Emerging market equities continued to underperform their developed market counterparts as the former was dragged down by Chinese stocks. Visio Capital, in their monthly commentary, further reported that local equities held up well as banks and index heavyweight Richemont rallied.

commentary, further reported that local equities held up well as banks and index heavyweight Richemont rallied.

The MSCI World Index returned +8% in US$, boosted by the US with the S&P500 Index up 9% and the tech-laden Nasdaq 100 up 12.5%. This is now well above the recent lows but still down more than 10% year-to-date. As mentioned earlier, emerging markets and Asia remained weak, with the Hang Seng index losing another 7.8% for the month, despite some improvement in COVID-19 lockdowns in China.

South African bonds did better than most of their global counterparts in what was a particularly volatile month. By mid-July, the All Bond Index was down 2.6% before rallying 5.0%, buoyed by the SARB’s repo rate hike among other factors. The property sector was the best-performing domestic asset class, but elevated volatility makes it unattractive for investors who focus on income with stable capital values.

Laurium Capital reports that looking ahead at equities, it is unlikely that global investor risk appetite will improve significantly without political (and/or military) peace in Ukraine/Europe, and Asia. Until then, energy markets will remain a major focus (constrained gas supplies from Russia to the EU in particular), with rationing and cost pressures suppressing consumer and corporate confidence and spending power into the Northern Hemisphere winter that lies ahead. The Chinese economy is another source of uncertainty, with ideology trumping economics in the short term. Fiscal stimulus will have to come soon to keep Chinese growth at targeted levels, and this will complicate the outlook for commodity prices despite tight supply. SA’s economic prospects remain highly sensitive to the future path of metal prices and the volume of mining exports.

This high level of uncertainty creates many opportunities for patient investors. It provides an opportunity for active managers to show their mettle versus passive investment funds.

- Source: Factset

- All performance numbers in excess of 12 months are annualised

- A negative number means fewer rands are being paid per US dollar, so it implies a strengthening of the rand.

Commentary: The future of electricity in South Africa

In a recent research note, the independent political and economic analyst JP Landman took an in-depth look at not only the issues that Eskom faces, but also the world beyond load shedding. In this month’s commentary, we publish a few extracts which focus on the world beyond load shedding.

In one week we had three big announcements on electricity in South Africa. First, the president addressed the nation and outlined how the government intends to deal with Eskom, load shedding and the future of the electricity industry. Two days later Eskom showed its hand at a coal transition indaba on how it sees the energy picture unfolding and what investment it would entail. The following day Treasury lifted the veil on its plans for Eskom’s debt. There is a remarkable alignment and consistency between the three announcements, and together they paint a clear picture of a huge game-changer for South Africa.

Firstly, we are moving from a state monopoly in electricity provision to a free market where people can risk their own money to build plants, generate power and sell it to their chosen customers. Customers will have the option to buy from different suppliers. Traders are already operating, connecting buyers and sellers of electricity. It is a remarkable change and brings South Africa in line with best practice elsewhere in the world, employed with great success from the Netherlands to China.

Secondly, we are moving from a coal-based electricity system to one based largely on solar, wind, and gas. Coal will still be used for a long time as both Medupi and Kusile are coal-fired and they have 40 years to run, but the switch is undeniable and irreversible. Coal’s share of our energy needs will decline from over 70% to below 50% and then decline further.

From being one of the biggest carbon emitters in the world, South Africa will become a country that is doing what is necessary to limit climate warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. This will protect our exports and give us access to markets that will increasingly be closed to non-compliant countries. Whether one produces wine or BMWs, if carbon-intensive electricity was used to produce them, access to some markets will suffer. Domestically, the switch will help to clean filthy air in parts of Mpumalanga and leave a healthier population. Concurrently, it will create more jobs in rural areas of the country.

Thirdly, all of this will unleash enormous investment acting as a spur for the country’s growth over the next decade and more. Eskom foresee R1,2 trillion investment over the next eight years to 2030. And that is only the beginning. More investment will take place after 2030. Already we have seen that local and overseas investors have a big appetite for investment in South African renewable energy – every single bid window so far is oversubscribed. Energy is the new investment frontier of South Africa, and it will do for the country what the discovery of minerals like diamonds and gold did. Just ignore those who lament that South Africa is not investable – the ground has already shifted under them; they just have not noticed yet.

Fourthly, the energy transition opens the way for industrialisation to follow in its wake. Solar panels, batteries, cables, and transmission lines or parts thereof can be manufactured here. A few examples: Swedish energy storage specialist Polarium opened a lithium-ion battery assembly plant in Montague Park, Cape Town. The world’s biggest vanadium producer, Bushveld Minerals, is engaged in electrolyte and battery manufacturing and is building a new factory in East London. The company wants to be more than a miner and become a big player in electricity storage.

Not all of this will happen without opposition – from coal mine owners to labor unions to politicians to the public. At the very least the policy direction is clear. And believe it or not – policy development in electricity supply is ahead of freight transport, ports and water. Electricity reform is clear evidence of how the government sees the role of new technology and private sector/government cooperation, and with some political will it could be the blueprint for significant economic growth in decades to come.

Page load link

tighter monetary policy drove a downward revision of 1.4 percentage points in the United States. In China, further lockdowns and the deepening real estate crisis have led growth to be revised down by 1.1 percentage points, with major global spillovers. And in Europe, significant downgrades reflect spillovers from the war in Ukraine and tighter monetary policy. Global inflation has been revised upwards due to food and energy prices as well as lingering supply-demand imbalances and is anticipated to reach 6.6 percent in advanced economies and 9.5 percent in emerging markets and developing economies this year. In 2023, disinflationary monetary policy is expected to bite, with global output growing by just 2.9 percent.

tighter monetary policy drove a downward revision of 1.4 percentage points in the United States. In China, further lockdowns and the deepening real estate crisis have led growth to be revised down by 1.1 percentage points, with major global spillovers. And in Europe, significant downgrades reflect spillovers from the war in Ukraine and tighter monetary policy. Global inflation has been revised upwards due to food and energy prices as well as lingering supply-demand imbalances and is anticipated to reach 6.6 percent in advanced economies and 9.5 percent in emerging markets and developing economies this year. In 2023, disinflationary monetary policy is expected to bite, with global output growing by just 2.9 percent. Despite these downward revisions, economic growth remains above a low rate of potential. Private investment has strengthened on the back of the recovery, but public sector investment remains weak. Household spending remains supportive of growth but is likely to soften next year due to higher inflation, lower asset prices, and rising interest rates. Tourism, hospitality, and construction should see stronger recoveries as the year progresses.

Despite these downward revisions, economic growth remains above a low rate of potential. Private investment has strengthened on the back of the recovery, but public sector investment remains weak. Household spending remains supportive of growth but is likely to soften next year due to higher inflation, lower asset prices, and rising interest rates. Tourism, hospitality, and construction should see stronger recoveries as the year progresses. commentary, further reported that local equities held up well as banks and index heavyweight Richemont rallied.

commentary, further reported that local equities held up well as banks and index heavyweight Richemont rallied.