Economic and market overview

Global

Continued worries about inflation, the spread of the Delta variant of Covid-19, and rising tensions in the Middle East dominated headlines in July.

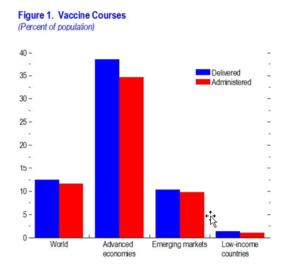

The International Monetary Fund published an update to their World Economic Outlook during the month and looking beyond the headlines mentioned above, identified the further divergence in vaccine access as the principal fault line along which the global recovery splits the world into two blocs. On the one hand, there are those that can look forward to further normalization of activity later this year (almost all advanced economies), and on the other, those that will still face resurgent infections and rising COVID death tolls. The recovery, however, is not assured even in countries where infections are currently very low so long as the virus circulates elsewhere.

The IMF projects growth of 6% in the global economy in 2021 and 4.9% in 2022. Prospects for emerging markets and developing economies have been marked down for 2021, especially for Emerging Asia. By contrast, the forecast for advanced economies has been revised up. These revisions reflect pandemic developments and changes in policy support.

Recent price pressures for the most part reflect unusual pandemic-related developments and transitory supply-demand mismatches. Inflation is expected to return to its pre-pandemic ranges in most countries in 2022 once these disturbances work their way through prices, though uncertainty remains high. Elevated inflation is also expected in some emerging markets and developing economies, related in part to high food prices. The trajectory for inflation is likely to remain an important discussion point as markets navigate their way to the end of the year.

South Africa

The South African Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to leave the repurchase rate unchanged, keeping it at 3.5%.

Governor Lesetja Kganyago stated that, despite steady improvements in vaccination rates, stronger confidence, and better global economic growth, the Covid-19 virus continues to weigh on global prospects. Vaccination rates are lagging in many emerging markets and developing countries. Until populations develop sufficient immunity to curb virus transmission, waves of infection are likely to continue. As indicated by South Africa’s public health authorities, the third wave of virus infection is currently declining. Additionally, by raising uncertainty and reducing investor confidence, the recent unrest in parts of the country is likely to slow our ongoing recovery.

The Reserve Bank expects GDP to grow by 2.3% in 2022 and by 2.4% in 2023, which significantly lags the expected global growth rates mentioned on the previous page. It’s not all bad news though, as the risks to the medium-term domestic growth outlook are assessed to be balanced. High export prices, stronger household incomes, and a somewhat better investment outlook are backed up by generally supportive global conditions, despite ongoing financial volatility. Recent events in the country, their impact on vaccinations, a longer than expected lockdown, limited energy supply, and policy uncertainty pose downside risks to growth.

somewhat better investment outlook are backed up by generally supportive global conditions, despite ongoing financial volatility. Recent events in the country, their impact on vaccinations, a longer than expected lockdown, limited energy supply, and policy uncertainty pose downside risks to growth.

After 14 years of construction (and a lot of controversies), Eskom has announced that the construction of the Medupi Power Station in Lephalale, the biggest dry-cooled and most expensive power station in the world, has been completed. Medupi is a nearly 4 800 Megawatt power behemoth whose rampant appetite for coal will increase by 16-million tons a year. Completion was announced after Unit 1, the last of six generation units of the project, finally attained commercial operation status at the end of July. Despite a bleak future for fossil-fueled power generation, South Africa’s economy will benefit from the increased certainty in electricity supply. It should be cause for celebration. But South Africans, weary of persistent load shedding and escalating electricity costs, can be forgiven for their reluctance to applaud. The project took double the time and three times the cost to complete. That, however, is water under the bridge and for now, the completion is a silver lining in an otherwise grey economic sky.

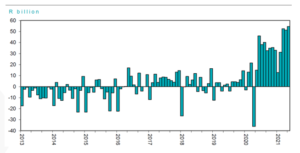

Lastly: South Africa’s trade balance remains in positive territory as the chart below (from Kevin Lings at Stanlib) shows:

This is a phenomenon that counteracts some of the negative developments in recent months and has certainly aided the rand to remain fairly strong against developing market currencies.

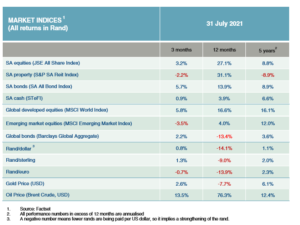

Market Performance

Equity markets in the developed world had another strong month (up 1.8%), despite rising concerns surrounding the impact of the COVID-19 Delta variant on the global economic recovery. Emerging markets, on the other hand, gave up most of their year-to-date gains as Asian markets, in particular, detracted from returns. The MSCI Emerging Market Index ended the month nearly 7% lower, as concerns about regulatory intervention in technology companies caused sell-offs across a broad range of Chinese listed shares.

Despite the looting of retailers in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng early in July, coupled with the poor performance of Naspers and Prosus, the South African equity market bucked the trend of its emerging market peers – the JSE All Share Index gained over 4% during the month. This was mainly driven by a very strong showing of the resource sector (up 11.7%).

The property sector was the worst-performing domestic sector (-0.6%) as it bore the brunt of the unrest. The sector did recover some of its losses as the unrest subsided and the full extent of the damage became apparent, and properties returned to operation in the affected areas.

Laurium Capital reports that, on the fixed interest side, US bond yields continued to trade at stronger levels in July. The Federal Open Market Committee meeting provided little new information on the timeline for tapering or interest rates increases. Market expectations for tapering to begin late this year or early next year seem to remain intact.

The Federal Open Market Committee meeting provided little new information on the timeline for tapering or interest rates increases. Market expectations for tapering to begin late this year or early next year seem to remain intact.

Commentary – What to do about the Chinese situation?

Naspers and Prosus have enjoyed a lot of attention in recent weeks as Chinese regulators clamped down on a wide range of technology companies. In the following article by Piet Viljoen, Value Strategy Manager at Counterpoint Asset Management, he analyses the situation and proposes a course of action which a value investor may want to follow to manage the inherent risks associated with an investment in these two companies.

This article was originally published by Counterpoint Asset Management in their Counterpoint Investment Insights for August 2021

“Recently, some Chinese companies have become problematic investment propositions for global investors. This situation is exacerbated in South Africa, where Naspers – and its sister creation straight out of Dr. Frankenstein’s lab – Prosus, have a large shareholding in a Chinese company.

Naspers, as I’m sure readers will know, made one of the single best investment decisions in history when it bought 32,8% of a Chinese business called Tencent for US$20 million in 2001. Today, that investment is worth US$200 billion, i.e., a 10 000 bagger. In investment parlance, a ten-bagger is an investment that goes up by a multiple of ten times and is a rare achievement – making a 10 000 bagger extra special. Simply put, a 10 000 bagger turns a thousand dollars into a million. Talk about unicorns!

32,8% of a Chinese business called Tencent for US$20 million in 2001. Today, that investment is worth US$200 billion, i.e., a 10 000 bagger. In investment parlance, a ten-bagger is an investment that goes up by a multiple of ten times and is a rare achievement – making a 10 000 bagger extra special. Simply put, a 10 000 bagger turns a thousand dollars into a million. Talk about unicorns!

Individuals can exceptionally become bond issuers if they have an attractive enough pool of assets they can securitize to back up the bonds. This was the case with Bowie. Moreover, one of the reasons bonds are so attractive as a financial instrument is that they can be liquidated at any time after purchase: unless the issuer defaults, which is rare, institutions or retail investors can always recover their loan if they themselves need cash at short notice.

It should come as no surprise that Naspers/Prosus is a popular investment in South African portfolios. Moreover, because of the fantastic performance of Tencent, they occupy very large positions in benchmark indices to which investors compare their efforts. A quick perusal of the biggest funds in South Africa shows that they have allocations of between 10% and 20% to these investments. And some funds have more. As such, South African investors have huge exposure to the “Chinese situation”, even in their domestic investments.

But what exactly is this “Chinese situation”, and why is it problematic? Most knowledgeable investors will point out that Tencent has evolved into one of the best businesses in the world. So what’s the problem? To understand why it’s worth a cursory look under the hood. Tencent is a Chinese holding company that is the world leader in gaming and runs the largest messaging, social networking, and mobile payments platform in China. It also invests capital in the next generation of companies in China and around the globe. Tencent combines the diversification of an old-school conglomerate with the growth and decentralization of an internet-native business.

In China, Tencent is like Facebook, Nintendo, Shopify, Netflix, Spotify, Slack, and PayPal rolled into one. Its flagship product, WeChat, has 1.2 billion users, and those users spend more time in the app every day than Americans spend on all social media apps combined. Businesses in China run on WeChat. They can communicate with customers, get distribution, build entire functioning products, and accept payments through WeChat Pay. WeChat is Tencent’s unfair advantage in China. It’s at the top of Tencent’s acquisition funnel. Three of Tencent’s four largest holdings – Meituan Dianping, JD.com, and Pinduoduo – are Chinese e-commerce businesses that run on top of WeChat.

So, not only does Tencent have an enviable core business, but it is also in a privileged position enabling it to acquire investments in other businesses on favourable terms. It’s clear that Tencent is in a particularly advantaged competitive situation and should carry a valuation premium to reflect its historic high rates of growth as well as the high growth expected to materialise as a result of its dominance in a large market.

As they say, the devil is always in the details. Unfortunately, non-Chinese shareholders are not allowed to own shares in companies in certain sectors in China, by governmental decree. Tencent is one of those companies. The Chinese government wants to encourage capital inflows, so they turn a blind eye to the structure that allows foreign investors (such as Naspers) to gain access to investments in Chinese businesses.

This structure is called a VIE (“Variable Interest Entity”). VIE’s do not represent actual ownership but are contracts that allow access to the corporations’ cash flows. In this structure, the onshore Chinese company is capitalised by a foreign shell company – generally a Cayman-listed entity. Which, in turn, owns a contractual agreement with the nominee shareholders of the China-based business (the VIE), which confers some rights: substantially all the economic benefits and all the expected losses of the China-based business – in short, a contractual interest but not an ownership interest.

It’s important to note that VIE’s are illegal instruments historically tolerated by the Chinese government. China’s door is generally closed to inbound traffic – internet content and other forms of media as well as channels of cultural influence. For capital, the inbound door remains wide open, but the way out is increasingly shut. Policies around IPO approvals, VIEs, internet control, anti-monopoly regulation, and investment policy have everything to do with capturing and holding on to hard currency inflows. China needs this, as their current account surplus shrinks, and (illegal) capital outflows from private individuals intensify.

Commentary – What to do about the Chinese situation? (continued)

Despite their questionable legal position, VIE listings have generally provided good returns to underwriters and investors. VIEs worked because prospective profits trumped fear of regulatory scrutiny. Worrying about the details of ownership structures can come later. Unfortunately, Chinese regulators have become increasingly interventionist, curbing the economic and social power of China’s once-loosely regulated internet giants. The first warning shots were fired in 2018 when curbs on the online gaming industry were introduced. Last year, the IPO of ANT Financial, the financial services arm of Alibaba was pulled. Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba and owner of ANT, remains unaccounted for. Last month, the CAC – “Cyberspace Administration of China” (!) – announced it had launched an investigation into Didi on suspicion the company had violated national security laws. This happened two days after it was listed in the USA and caused a 50% decline in its share price.

At roughly the same time, the Chinese antitrust regulator ordered Tencent Music group to give up exclusivity on its labels, causing a 60% decline in its share price. And, even more recently, China’s ban on private education, caused declines of over 50% in a slew of listed education companies. It’s clear the time to worry about the details has now arrived: recent crackdowns show that Chinese authorities are more concerned about policy than market prices, and Chinese authorities may still decide they have no further need for VIE structures. If this were to happen, the value of Tencent to foreign investors – including Naspers/Prosus- could be zero.

declines of over 50% in a slew of listed education companies. It’s clear the time to worry about the details has now arrived: recent crackdowns show that Chinese authorities are more concerned about policy than market prices, and Chinese authorities may still decide they have no further need for VIE structures. If this were to happen, the value of Tencent to foreign investors – including Naspers/Prosus- could be zero.

Let me say that word again – zero. Yes, the Naspers/Prosus investment in Tencent faces existential risks. This is very different from normal market volatility, where the prices of good quality businesses like Tencent can decline sharply, but then recover again over time. When governments appropriate your assets for policy purposes, you generally get nothing in return.

So we have a type of Schrodingers cat situation here – in one state, Tencent is a valuable business, in another, it is worthless (to Western Investors, at least). The question thus becomes – how do you manage this risk?

One of the ways to manage risk in a portfolio context is to use position sizing. A good way to deal with the Chinese situation would be to not have it as the single largest portfolio position. That is, not if you are investing as a principle. It’s understandable – albeit unforgivable – if agents, who manage money on behalf of other people, do so if the benchmark demands it.

A small position – if it were cheap enough to own – seems eminently sensible in a portfolio context. Here the risk of Tencent going to zero is very different from other risks embedded in the portfolio, providing diversification benefits. And, if it does happen, the small position protects the overall portfolio from suffering a significant loss. If the Chinese government continues to ignore VIE’s, then the portfolio will also benefit.

In the various Counterpoint Value fund strategies we have never held Tencent directly (and have only held smaller positions in its proxies Naspers/Prosus) as we believed the valuation premium the market placed on Tencent was too high. Now, with the benefit of hindsight, it’s clear that we consistently underestimated the intrinsic value and growth potential of the business.

Accordingly, our funds have not participated in many of the 10 000 bags that Naspers shareholders historically enjoyed and this mistake of omission has cost our investors. But that is now water under the bridge. Given the recent sharp decline in the share prices of companies associated with VIE’s there might be a case on valuation grounds for owning some shares in the Tencent/Naspers/Prosus nexus. But – the existential risk has also increased substantially.

Ignoring index weightings and sizing positions appropriate to one’s own risk appetite and thinking about how this risk interacts with other risks embedded in one’s portfolio, seems like a responsible way of dealing with this particular Chinese situation.”

Source and disclaimer: https://cpam.co.za/what-to-do-about-the-chinese-situation/